|

Introduction

Falls are one of the most common and problematic issues

among older adults (1,2). Generally, one third of community

dwelling older adults had one or more falls each year

(3-6). Falls were the leading cause of injury-related

visits to emergency departments in the United States

(7). Using data from the National Health Interview Survey,

approximately 45% of all injuries in the home environment

leading to medical attention were falls (8). In fact,

20% of nonfatal home falls that require

medical attention occur in the over 75 age group (8).

Moreover, it has been noted

that among individuals who fall, there is a high percentage

(40-73%) who have a fear of falling. It has also been

reported that up to half of older adults who have never

fallen have a fear of falling (3,9). Fear of falling,

whether or not related to a previous fall, can have

a major impact on older adults. Fear of falling may

be a reasonable response to certain situations, leading

elderly persons to be cautious, and can contribute to

fall prevention through careful choices about physical

activity (10). Within this context, fear represents

a reasonable reaction to possible danger and has few

negative consequences as long as physical and social

mobility remains unaffected. However, the fear of falling

can initially present or progress beyond this point

to become a debilitating condition.

In particular, fear of falling

has been associated with negative consequences such

as reduced activity of daily living (11,12), reduced

physical activity (2,13-15), lower perceived physical

health status (16), lower quality of life (2,11), and

increased institutionalization (2,11)

There are many factors associated

with fear of falling, and there are a number of reported

prevention or intervention programs for fear of falling.

However, there is not, as yet, a comprehensive review

of these factors.

Evolution

of the Concept

Despite the importance of the percentage and the consequences

of fear of falling, its definition is still vague and

warrants clarification.

In the late 1970s, Marks and Bebbington described "space

phobia" in four elderly women who had intense fear

of falling "when there was no visible support at

hand or on seeing space cues while driving" (17).

These authors speculated that space phobia "might

be a hitherto unrecognized syndrome or an unusual variant

of agoraphobia". Fear of falling has gained increasing

attention in the public health literature over the past

two decades. The concept was introduced by Bhala, O,

Donnell, and Thopil (18) who used the term "ptophobia

which means a phobic reaction to standing or walking.

Murphy and Isaacs (1982) called it the "post-fall

syndrome" in which elderly people who had fallen

developed severe anxiety that affected their ability

to stand and walk unsupported (19). Subsequent research

demonstrated that elderly people can develop fear of

falling even when they have not fallen (20-22). Other

authors have stated that fear of falling means a patient's

loss of confidence in his or her balance abilities (21,23).

Tinetti and Powell (24) depicted fear of falling as

a progressing worry about falling that at last prompts

evasion of the execution of daily activities. As indicated

by Tidieksaar (25), fear of falling alludes to an un-sound

absence of movement evasion because of dread of falling.

Over the years, various definitions

of fear of falling have evolved. Some authors have focused

purely on the fear (26), while others have included

avoidance of activities as a consequence of the fear

(27). A few authors have eschewed the term "fear"

and have instead focused on the person's loss of confidence

in balance and walking (28,29). Currently the term fear

of falling is used to describe an exaggerated concern

of falling that leads to excess restriction of activities.

The fearful older adult narrows their world, resulting

in isolation and ultimately physical and functional

decline.

So the fear of Falling (FoF)

or Post Fall Syndrome or Psychomotor Regression Syndrome

(PRS) is defined as: "Decompensation of the systems

and mechanisms implicated in postural and walking automatisms

(30)". It appears either insidiously due to an

increase of frailty or either brutally after a trauma

(fall) or an operation. This syndrome is composed of

a combination of neurological signs, motor symptoms

and psychological disorder.

Epidemiology

Among community-dwelling elderly, fear of falling is

frequent, with prevalence ranging from 21 to 61% in

community-based epidemiologic studies (3,20, 26-29,

30). Community studies that are limited to elderly people

who have actually fallen have reported prevalence rates

of 32-83% (31,32). Strikingly, 33-46% of community-dwelling

elders who have not fallen also report fear of falling

(20,21).

Among selected populations, fear of falling has been

found among 46% of nursing home residents, (33) 47%

of persons attending a dizziness clinic,(34) 66% of

patients on a rehabilitation ward,(35) and 30% of hospitalized

elderly patients without a specific diagnosis (40% of

those who had fallen and 23% of those who had not fallen).(11).

Some of these prevalence rates may actually be underestimates,

since people who are most fearful may be less likely

to participate in research studies.

Among elderly persons who are afraid of falling, up

to 70% (20,27,26,30,35) acknowledge avoiding activities

because of this fear. In some cases, individuals become

housebound as a result of their fear. Activity restriction

is, in itself, a risk factor for falls because it can

lead to muscle atrophy, deconditioning and poorer balance

(21, 31). Curtailment of activities can also lead to

social isolation (36). Thus, fear of falling can contribute

to both functional decline and impaired quality of life.

Although a higher prevalence of 40-73% has been reported

in people who have fallen, studies have shown that up

to half of people with fear of falling have not experienced

a fall. These people have likely had a friend or family

member or fellow nursing home resident experience a

fall and have seen the medical and social consequences

for that person.

(3,9,26,36).

Manifestation

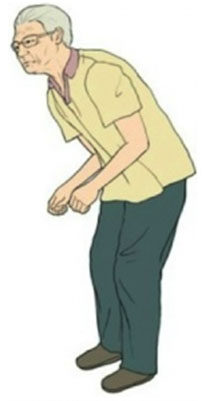

Motor symptoms

Standing

• "Retropulsion" (gravity center kept

backward)

• Posterior instability (tendency to fall backward)

• Both leading to postural compensation (Knees/hips

kept flexed and bend forward) and to this traditional

posture:

Typical anterior/flexed posture

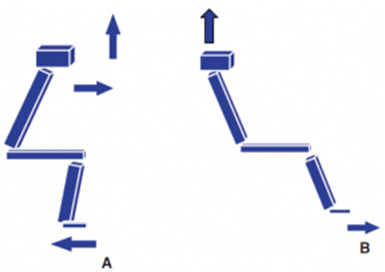

Sitting

• Impairment of sitting posture is less visible

but as problematic

• Patients with PRS keep their buttocks forward,

shoulders backward and feet far from the seat (image

B)

• However, to stand up we need to transfer our

gravity center forward (image A)

• Therefore, standing up is difficult/impossible

without exterior help for patients with PRS (image B)

A: normal way of

standing up B: wrong way of standing up

Walking

It is difficult for them to

• Initiate the walk (they look like they freeze)

• Difficulty to avoid obstacle and to turn

Gait

•  length of the step

length of the step

•  knees and hips flexion (

knees and hips flexion ( trip risk)

trip risk)

•  heel strike

heel strike

•  time spend in bipodal stance (

time spend in bipodal stance ( posterior instability)

posterior instability)

Neurological signs

o Alteration or absence of postural adaptation (the

person is not able to balance

themselves and to stand up without falling).

o Protective reaction (put their arms in front when

falling to slow the fall)

Psychological disorder

Patient with PRS present with

•

Anxiety/phobia of verticality (afraid to stand

up)

• Loss of self-confidence/self-esteem

• Loss of motivation

associated with a reduction of their activity and social

interaction

Therefore, they end up in a

vicious circle

•

They are afraid to move

• They move

less

• They become

even less able to move and even more afraid

Evaluation

Measurement issues relating to fear of falling

A number of measures have been

developed to measure fear of falling. Each of these

measures uses different definitions and premises. Fear

of falling measures are conceptualized based on the

definition of fear of falling, "fearful anticipation

of a fall" (37), whereas self-efficacy and confidence

measures are based on the individual's confidence or

belief in their ability to perform specific activities

without losing balance or falling.

The FES (28) and Activities-Specific

Balance Confidence Scale (ABC) (38) were developed for

measuring fall related self-efficacy. The FES and ABC

scales have been used repeatedly with community dwelling

older adults (11,13,39-45). Fall-efficacy and confidence

measures, however, may not be a true conceptualization

of fear of falling because it is possible that older

adults feel confident in their abilities to engage in

an activity without "being concerned" about

losing balance or falling, but that they could still

be fearful of having a fall. Additionally, a fear-related

self-efficacy measurement may not be a true conceptualization

as the relationship between the fear of falling and

the self-efficacy to engage in activities is likely

to be strongly influenced by physical function and health

status.

Fear of falling measures

Single item question

The simple question, "Are you afraid of falling?"

was used initially in-research studies with a "yes/no"

or "fear/ no fear" response format (3,40,46).

The advantage of this format is that it is straight

forward and easy to obtain responses. It is limited,

however, as it is not possible to detect variability

in degrees of fear (47), and has an uncertain relationship

to behavior (28). In an attempt to overcome this limitation

some researchers have utilized this single item question

with a Likert scale response pattern (i.e. "not

at all afraid," "slightly afraid," "somewhat

afraid," and "very afraid") to reflect

the degree of fear (45,48,49).

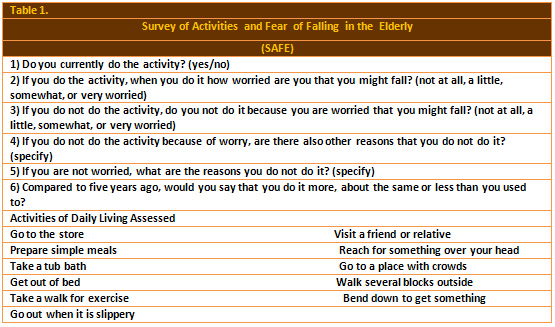

Survey of Activities and fear of falling

in the Elderly

The new instrument Survey of Activities and fear of

falling in the Elderly (SAFFE, Table 1) scale was developed

to assess the role of fear of falling in activity restriction

(50). The SAFFE uses the premise that there are negative

consequences to fear, such as activity restriction or

poor quality of life. The instrument evaluates fear

of falling through the performance of 11 activities

of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living,

mobility tasks, and social activities (i.e., taking

a shower, going to the store, taking public transportation,

and going to movies or shows). Based on the assumption

that activity avoidance may be an early sign of fear

of falling, the SAFFE measures information about participation

in exercise activities and social activities. The SAFFE

has 11 activity items, and for each activity several

questions are asked: (a) Do you currently do it? (yes

or no); (b) If you do the activity, when you do it how

worried are you that you might fall? (0 not at all worried,

1 a little worried, 2 somewhat worried, and 3 very worried);

(c) If you do not do the activity, do you not do it

because you are worried that you might fall? (0 not

at all worried; 3 very worried); (d) If you do not do

the activity because of worry, are there also other

reasons why you do not do it? (if yes, specify); (e)

For those who are not worried, why do you not do it?

(specify); (f) Compared with 5 years ago how often do

you do it? (1 more than you used to, 2 about the same

or 3 less than you used to). However, SAFFE is so complicated

that it is not easy to administer to the elderly. Also,

it is difficult to compute the SAFFE score, because

it is made up of a skip pattern (51). The questions

(a), (b), and (f) determine activity level, fear of

falling status, and activity restrictions, while questions

(c), (d), and (e) examine the number of activities that

are not done because of other reasons in addition to

fear of falling. In addition, the scoring range is 0-33.

SAFFE is not perfect since the instructions on measurement

do not elucidate whether activity and social activity

should be divided when it is computed. Furthermore,

there is no definition of a cut off score that means

fear of fall vs. non fear of fall status. Moreover,

SAFFE measures the degree that elderly feel worry during

periods of activity, while fear of falling while inactive

status is not measured.

The University of Illinois

at Chicago Fear of Falling Measure

Velozo and Peterson (52) developed

the University of Illinois at Chicago Fear of Falling

Measure (UIC FFM) for the community dwelling elderly.

It comprises 16 items and centers on the older adults'

ability to perform activities of daily living. The measure

asks the participants to indicate how worried they would

be if they were to perform the activities. It is a four-point

rating scale. The evidence of reliability of the UIC

FFM was provided by alpha coefficient ( 0.93) (Velozo

& Peterson), but the authors did not report any

evidence of validity.

Fall efficacy measures

Fall efficacy has been used

to measure fear of falling in many studies. However,

as noted before, its conceptualization differs from

fear of falling. Tinetti et al. (28) developed the FES.

The FES is a 10 question scale, and the scores are summed

to give a total score between 0 and 100. Although many

authors have used the FES scale (11,13,40-42,44,45,53),

the measurements are limited because the 10 items measure

only simple indoor activities. The FES, therefore, is

not appropriate for use with older adults who spend

time outside the home and have high mobility (47). An

upgraded version, the modified FES (mFES), contains

an additional four questions about outdoor activities

(29), and has been used in various settings (40).

Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale

Powell and Myers (38) developed

the ABC for older adults with greater functioning, based

on the definition of fall related self-efficacy as the

FES. It is a 16-item questionnaire with a visual analog

scale (0-100). The 16-item activities are more specific

than those of the FES. The activities were performed

outside of the home and were more challenging than those

in the FES (16,43).

Fear of falling is one of the

major issues relating to the overall health of older

adults. Fear of falling leads to physical and psychological

problems, and despite the large number of older adults

who suffer from the serious consequences of fear of

falling, its definition is still vague and warrants

clarification. From the literature review, it can be

seen that the most widely used fear of falling measurements

involve the evaluation of fear of falling and fall efficacy.

These measurements need to be used appropriately, based

on the correct definition of fear of falling. Normally,

fear-related efficacy was measured with exact measurements,

such as FES and ABC (54,55). However, when the study

related to the measurement of fear of falling, these

measurements were often misused. Fear of falling was

regularly measured with either fear of falling instruments

(50) or fall efficacy measurements (56-58).

Due to the misinterpretation

and the misapplication of measurements, the percentage

of people suffering from fear of falling may have been

underestimated or overestimated. Therefore, in future

research the question of whether or not the FES accurately

measures fear of falling must be considered. This can

be accomplished by applying both fear of falling measurements

and fall efficacy instruments to the same study participants.

Moreover, nurses working closely with older adults need

to be aware of the different definitions of fear of

falling and the FES. Although older adults may have

a fear of falling, they may also have confidence in

their capabilities to perform activities without falling.

Therefore, nurses may be able to encourage sedentary

older adults who have a fear of falling to perform specific

activities that reinforce confidence with regard to

not falling. Differentiating between the meanings of

fear of falling and fall efficacy is very important

when encouraging older adults to participate in certain

activities. In short, fear of falling needs to be measured

accurately with fear of falling instruments. In addition,

fall efficacy or confidence as it relates to activities

that can be performed without fear of falling should

be measured by using the FES in an effort to clearly

define each variable.

Assessment

Tools

Several approaches to the assessment and measurement

of fear of falling have been used and may partly explain

the variability in the prevalence rates reported above.

The easiest way is to ask subjects the following question:

"Are you afraid of falling?" An annex of this

definite method is to rate the severity of fear, ranging,

for example, from mildly, moderately or very afraid.

Though a direct question is simple, up-front and simply

produces prevalence estimates, this method lacks the

sensitivity of a continuous measure. Tinetti and colleagues

operationalized fear of falling as low perceived self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy refers to an individual's perception of

capabilities within a particular domain of activities

(59). Tinetti, et al. developed the Falls Efficacy Scale

(FES), a 10-question self-rated scale assessing a person's

confidence in performing activities in the home (e.g.,

"How confident are you that you can take a bath

or a shower without falling?"). (28). The subject

rates each question from 1 to 10, resulting in a summative

global score whereby a higher score is reflective of

lower confidence. The scale has been modified for patients

with strokes [FES (S)] (60) and to include outdoor activities

(MFES). (29).

In 1995, Powell and Myers developed the Activities-specific

Balance Confidence Scale (ABC); also based on the self-efficacy

concept (38). This 16-item scale contains a broader

range of activity difficulty and more detailed activity

descriptors than the FES. It has greater reliability

than the FES in detecting loss of confidence in seniors

who are otherwise highly functioning (38).

Lachman, et al. developed the Survey of Activities and

Fear of Falling in the Elderly (SAFFE, table 1), which

examines 11 activities of daily living, instrumental

activities of daily living, mobility tasks and social

activities, using the questions listed in Table 1 for

each activity (50). In contrast to the FES, the SAFE

does not require subjects to make hypothetical responses

about activities that they do not actually perform.

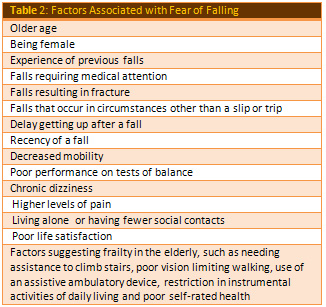

Associated Factors and Comorbidities

Only 10-15% of falls result in fractures or soft tissue

injuries severe enough to cause immobilization or hospitalization

(61). Thus, factors other than physical injury also

play a role in the development of fear and restriction

of activities following single or repeated falls. To

date, studies that have examined correlates of fear

of falling have primarily focused on demographic, physical

and social variables. Multiple variables have been found

to be associated with fear of falling, including those

listed in Table (2) (20,27,28,32,34,35). Thus, like

falling itself, fear of falling is multifactorial in

origin.

A few studies have also employed depression and anxiety

screening scales (4, 7,9,14,16,17). Most, but not all,

of these studies found more severe scores of depression

and/or anxiety among persons with fear of falling compared

with those who are not fearful. In these studies, depression

and anxiety scores were highly correlated. Dowton and

Andrews found that, of eight variables studied, depression

and anxiety scores were the two most important predictors

of chronic dizziness which, in turn, was significantly

associated with fear of falling (20). One study found

that fallers with a fear of falling were significantly

more likely to score above 11 on the Geriatric Depression

Scale (26). This score is frequently used as a cut-off

point to indicate mild or more severe depression, raising

the possibility that minor or major depressive disorders

may be more prevalent among fearful than non- fearful

fallers. However, to date there has been no attempt

to actually determine, by means of diagnostic interviews,

whether depressive and anxiety disorders are more prevalent

in fearful fallers. Furthermore, there has been no attempt

to determine whether specific personality traits or

coping styles predict fear of falling.

Risk factors for fear of falling

Several factors that have been

reported to influence fear of falling including:

Demographic influence

Increased age has been linked to increase in the fear

of falling (3,9,48). However, in studies by Kressig

et al. (41) and Andresen et al. (56), no significant

correlation was found between age and fear of falling.

In addition, women were regularly more likely to be

fearful of falls than men in several studies (3,15).

History of falls

Having had a previous fall was consistently correlated

with a fear of falling (3,15,48,56). Furthermore, multiple

fallers and those who had a harmful fall had a higher

chance of developing a fear of falling than single fallers

(15). However, there are also individuals who have not

fallen who account fear of falling (3,9,48).

Physical health

Fear of falling has been considerably associated with

health status (3,11,15). Those with lower alleged health

status were more liable to have a fear of falling (48).

For instance, Cumming et al (11) completed a prospective

study over 1 year with older adults who had received

medical intervention at the baseline of study. They

found that those who had low fall-related self-efficacy

were more likely to have a poorer health status measured

by health-related quality of life measures and SF-36.

Furthermore, in a study by Fletcher & Hirdes,(15)

poor perceived health status was found to be a risk

factor for activity limitations due to fear of falling

(odds ratio 1.82; 95% confidence intervals 1.47-2.26).

Morbidity

Fear of falling is more prevalent in persons with a

history of neurological problems (i.e., stroke and Parkinson's

disease), cardiac disease, arthritis, osteoporosis,

cataracts/glaucoma, visual and cognitive impairments,

and acute illness (3,11,15,56,61,62). These medical

ailments effect balance and function and hence augment

the individual's fear of falling. Patients with impaired

gait had a greater risk of fear of falling (15,31).

In addition, impaired mobility was associated with a

fear of falling (56,61).

The impact of mood on fear

of falling

Depression and anxiety were emphatically connected with

fear of falling among community dwelling older adults

(41,48,56,63-65). In spite of the fact that a causal

connection amongst depression and fear of falling can't

be deduced from cross-sectional investigations, it is

likely that fear of falling can prompt movement limitation

or social separation, which at that point brings about

discouragement in the elderly (64,66). It has likewise

been speculated that depression and/or the prescription

being take to treat depression adds to falls and a related

fear of falling (64).

The impact of exercise on fear of falling

Fear of falling decreases in older individuals engaged

in exercise programs, including activities to ameliorate

lower limb strength, balance, stability, and continuance,

or Tai Chi exercises (16,42,45,53,67). It is likely

that these activities upgraded lower leg quality, strolling

speed, adjust control, and physical capacity, which

diminished fall rates, and diminished the probability

of a related fear of falling.

Cognitive status

Fear of falling is predominant in older adults, and

may be even more common in populations known to have

balance problems, such as is the situation in individuals

with Parkinson's disease and dementia patients (68).

While cognitive status has not

reliably been related with fear of falling, the reality

of the matter is that some studies point to cognitive

status just like a critical factor in connection to

fear of falling among older adults in the community

(31,68). Specifically, fear of falling was more apparent

in Parkinson's patients with gait impairment than in

healthy older adults (68).

However, fear of falling with

active restriction was not related with older adults'

reported memory problems (12,15). It might be that fear

is extremely founded on cognitive function, but asking

questions relating to fear of falling to persons with

dementia poses a problem since their answers may not

be valid.

Management

Despite the high prevalence of fear of falling and its

associated morbidity, there has been little research

into its management.

Two fall prevention studies included falls efficacy

or fear of falling as a secondary measure. Tinetti,

et al. found that a multiple risk factor intervention

strategy resulted in a significant reduction in risk

of falling and a significant improvement in FES scores

among elderly people living in the community (69). On

the other hand, Reinsch, et al. found that a combination

of exercise, education and relaxation training did not

have a significant effect on the probability of falling

or fear of falling (70).

Three randomized controlled trials have examined the

effect of interventions on falls efficacy and/or fear

of falling as the primary outcome variable. Tennstedt,

et al. evaluated an intervention specifically designed

to reduce fear of falling and improve self-efficacy

in a population of community-dwelling elderly who reported

restriction in activity due to fear of falling (53).

Their cognitive behavioural intervention program had

an immediate, but modest, effect in improving subjects'

self-efficacy and increasing their level of intended

activity. However, these positive effects were not present

at six-month follow-up. Wolf, et al. found a statistically

significant reduction in fear of falling, as well as

risk of falling, among elderly people randomized to

15 weeks of Tai Chi compared to those in the control

condition (45).

Finally, Cameron, et al. found that the use of hip protectors

in elderly women who had fallen in the previous year

had no statistically significant effect on fear of falling,

but was associated with improved self-efficacy (40).

On the basis of these studies, with their varied interventions

and disparate results, it is difficult to derive recommendations

regarding the management of fear of falling. The multifactorial

nature of fear of falling suggests that a multifaceted

approach utilizing both psychological and physical interventions

may stand the best chance of success, but this remains

to be determined in future research. Furthermore, it

is quite possible that the approach to managing fear

of falling in non-fallers will differ from the approach

needed for fallers.

A successful management for patient suffering from Post

fall syndrome is composed of:

o Exercise to stimulate movement and strength

o Postural work to fix the compensation

o Teaching patients the right maneuver on the change

of position to explain the easy

and safe way to stand up, sit down, and lie down.

o Attempt to correct their gait

There are a larger number of

modifiable risk factors (i.e., exercise, physical health,

morbidity, history of falls, and mood status) than non-modifiable

risk factors (i.e., demographic status and cognitive

status) related to fear of falling.

Therefore, the team working

with older adults must work with them to make positive

changes to these modifiable factors by improving and

augmenting their physical activity. Since, depression

is one of the critical issue linked to fear of falling

(71) any strategy to decrease fear of falling should

include depression management. A number of authors carried

a number of intervention studies with the aim of preventing

or managing fear of falling in older adults. It was

clear that exercise programs, including strength training,

balance, endurance, mobility, and Tai-Chi programs,

have confirmed effectiveness in decreasing fear of falling

in older adults (39,42,43,45,53,71,72,73). Furthermore,

a meta- analysis revealed that exercise intervention

is an effective way to diminish fear of falling (58).

In this study, combined exercise programs with education

and cognitive intervention were more effective than

exercise programs alone. Furthermore, exercise within

facility was less effective than home or community-based

exercise (58).

Therefore making information

about fall-related fear to older adults available within

the community will entice fallers to minimize fall-related

accidents and manage fear of falling by taking part

in regular physical activities.

Future

Directions

Fear of falling is one of the major issues relating

to the overall health of older adults. Fear of falling

leads to physical and psychological problems, and despite

the large number of older adults who suffer from the

serious consequences of fear of falling, its definition

is still vague and warrants clarification.

Further research is needed in order to better understand

the genesis of fear of falling, improve its management

and diminish its consequences. It would be of interest

to clarify variables that may predict which individuals

develop fear of falling as an "appropriate"

or "protective" response to falls versus those

in whom the fear is clearly pathological. A greater

research focus on the psychological and psychiatric

correlates of fear of falling would be helpful in this

regard. Furthermore, it will be important to determine

whether interventions that place greater emphasis on

the specific treatment of depression, anxiety, negative

cognitions and avoidant behaviors can result in improved

outcome among older people with fear of falling.

References

1. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society,

& American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Panel

on Falls Prevention. (2001). Guideline for the prevention

of falls in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics

Society, 49, 664-672.

2. Li, F., Fisher, J., Harmer,

P., McAuley, E., & Wilson, N. L. (2003). Fear of

falling in elderly persons: Association with falls,

functional ability, and quality of life. Journal of

Gerontology: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences,58,

283-290.

3. Friedman SM, Munoz B, West

SK, et al. Falls and fear of falling: Which comes first?

A longitudinal prediction model suggests strategies

for primary secondary prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1329-35.

4. Means, K. M., Rodell, D.

E., & O'Sullivan, P. S. (2005).

Balance, mobility, and falls among community-dwelling

elderly

persons. American Journal of Physical Medicine &

Rehabilitation, 84,

238-250.

5. Tinetti, M. E. (2003). Preventing

Falls in Elderly Person. The New England Journal of

Medicine, 348, 42-49.

6. Tromp, A. H., Pluijm, S.

M. F., Smit, J. H., Deeg, D. J. H. Bouter, L. M., &

Lips, P. (2001). Fall risk screening test: A prospective

study on predictors for falls in community-dwelling

elderly. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, 837-844.

7. Fuller, G. F. (2000). Falls

in the elderly. American Family Physician, 61, 2156-2168.

8. Runyan, C. W., Perkis, D.,

Marshall, S. W., Johnson, R. M., Coyne-Beasley, T.,

Waller, A. E., et al. (2005). Unintentional injuries

in the home in the United States: Part II: Morbidity.

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 281, 80-87.

9. Murphy, S. L., Dubin, J.

A., & Gill, T. M. (2003). The development of fear

of falling among community-living older women: Predisposing

factors and subsequent fall events. The Journal of Gerontology;

Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58, 943-947.

10. Murphy, S. L., William, C. S., & Gill, T. M.

(2002). Characteristics associated with fear of falling

and activity restriction in community-living older persons.

Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 50, 516-520.

11. Cumming RG, Salked G, Thomas

M, et al. Prospective study of the impact of fear of

falling on activities of daily living, SF-36 scores,

and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 2000;5:M299-305.

12. Martin, F. C., Hart, D.,

Spector, T., Doyle, D. V., & Harari, D. (2005).

Fear of falling limiting activity in young-old women

is associated with reduced functional mobility rather

than psychological factors. Age and Ageing, 34,281-287.

13. Bruce, D. G., Devine, A.,

& Prince, R. L. (2002). Recreational physical activity

levels in healthy older women: The importance of fear

of falling. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,

50, 84-89.

14. Delbaere, K., Crombez, G.,

Vanderstraeten, G., Willems, T., & Cambier, D. (2004).

Fear-related avoidance of activities, falls and physical

frailty. A prospective community-based cohort study.

Age and Ageing, 33, 368-373.

15. Fletcher, P. C. & Hirdes,

J. P. (2004). Restriction in activity associated with

fear of falling among community- based seniors using

home care services. Age and Ageing, 33, 273-279.

16. Brouwer, B., Musselman,

K., & Culham, E. (2004). Physical function and health

status among seniors with and without a fear of falling.

Gerontology, 50, 135-141.

17. Marks I, Bebbington P. Space

phobia: syndrome or agoraphobic variant? BMJ 1976;2:345-7.

18. Bhala, P., O, Donnell, J.,

& Thoppil, E. (). Ptophobia: Phobic fear of falling

and its clinical management. Physical Therapy,1982;

62(2),187-190.

19. Murphy J, Isaacs B. The post-fall syndrome: A study

of 36 elderly patients. Gerontology 1982;28:265-70.

20. Dowton JH, Andrews K. Postural

disturbance and psychological symptoms amongst elderly

people living at home. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1990;5:93-8.

21. Maki BE, Holliday PJ, Topper

AK. Fear of falling and postural performance in the

elderly. J Gerontol 1991;46:M123-31.

22. Lawrence RH, Tennstedt SL,

Kasten LE, et al. Intensity and correlates of fear of

falling and hurting oneself in the next year. J Aging

Health 1998;10:267-86.

23. Tinetti, M. E., Speechley,

M., & Ginter, S. F. (1988). Risk factors for falls

among elderly persons living in the community. New England

Journal of Medicine, 319,1701-1707.

24. Tinetti, M. E. & Powell,

L. (1993). Fear of falling and low self-efficacy: A

case of dependence in elderly persons. [Special Issue]

Journal of Gerontology, 48, 35-38.

25. Tideiksaar, R. (2002). Falling

in Older People: Prevention and Management. (3rd ed.),

New York: Springer.

26. Arfken CL, Lach HW, Birge

SJ, et al. The prevalence and correlates of fear of

falling in elderly persons living in the community.

Am J Public Health 1994;84:565-70.

27. Howland J, Lachman ME, Peterson

EW, et al. Covariates of fear of falling and associated

activity curtailment. Gerontologist. 1998;38:549-55.

28. Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell

L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J

Gerontol 1990;45:P239-43.

29. Hill KD, Schwartz JA, Kalogeropoulos

AJ, et al. Fear of falling revisited. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil 1996;77:1025-9.

30. Tinetti ME, Mendes de Leon

CF, Doucette JT, et al. Fear of falling and fall-related

efficacy in relationship to functioning among community-living

elders. J Gerontol 1994;49:M140-7.

31. Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero

LJ, et al. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility

in elderly fallers. Age Ageing 1997;26:189-93.

32. Drozdick LW, Edelstein BA.

Correlates of fear of falling in older adults who have

experienced a fall. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology

2001;7:1-13.

33. Franzoni S, Rozzini R, Boffelli

S, et al. Fear of falling in nursing home patients.

Gerontology 1994;40:38-44.

34. Burker EJ, Wong H, Sloane

PD, et al. Predictors of fear of falling in dizzy and

non-dizzy elderly. Psychol Aging 1995;10:104-10.

35. Clague JE, Petrie PJ, Horan

MA. Hypocapnia and its relation to fear of falling.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:1485-8.

36. Howland J, Peterson EW,

Levin WC, et al. Fear of falling among the community-

dwelling elderly. J Aging Health 1993;5:229-43.

37. Silverton, R., & Tideiksaar,

R. (1989). Psychosocial aspects of falls. In R. Tideiksaar

(Ed.), Falling in old age: Its prevention and treatment,

(2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

38. Powell EL, Myers AM. The

Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale.

J Gerontol 1995;50A:M28-34.

39. Brouwer, B., Walker, C.,

Rydahl, S. J., & Culham, E. G. (2003). Reducing

fear of falling in seniors through education and activity

programs: A randomized trial. Journal of American Geriatrics

Society, 51, 829-834.

40. Cameron ID, Stafford B,

Cumming RG, et al. Hip protectors improve falls self-efficacy.

Age Ageing 2000;29:57

41. Kressig, R. W., Wolf, S.

T., Sattin, R. W., O'Grady, M., Greenspan, A., Curns,

A., et al. (2001). Associations of demographic, functional,

and behavioral characteristics with activity-related

fear of falling among older adults transitioning to

frailty. Journal of American Gerontology Society, 49,

1456-1462.

42. Nitz, J. C., & Choy,

N. L. (2004). The efficacy of a specific balance-strategy

training programme for preventing falls among older

people: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Age and

Ageing, 33, 52-58.

43. Sattin, R. W., Easley, K.

A., Wolf, S. L., Chen, Y., & Kutner, M. H. (2005).

Reduction in fear of falling through intense Tai-Chi

exercise training in older, transitionally frail adults.

Journal of American Geriatric Society, 53,1168-1178.

44. Wilson, M-M. G., Miller,

D. K., Andresen, E. M., Malmstrom, T. K., Miller, J.

P., & Wolinsky, F. D. (2005). Fear of falling and

related activity restriction among middle-aged African

Americans. Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences

and Medical Sciences, 60A, 355-360.

45. Wolf, S. L., Barnhart, H.

X., Kutner, N. G., McNeely, E., Coogler, C., & Xu,

T. (1996). Reducing frailty and falls in older persons:

An investigation of Tai Chi and computerized balance

training. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 44,

489-497.

46. Evitt, C. P. & Quigley,

P. A. (2004). Fear of falling in older adults: A guide

to its prevalence, risk factors, and con- sequences.

Rehabilitation Nursing, 29, 207-210.

47. Legters, K. (2002). Fear

of falling. Physical Therapy, 82,264-272.

48. Lach, H. W. (2005). Incidence

and risk factors for developing fear of falling in older

adults. Public Health Nursing, 22, 45-52.

49. Rucker, D., Rowe, B. H.,

Johnson, J. A., Steiner, I. P., Russell, A. S., Hanley,

D. A., et al. (2006). Educational intervention to reduce

falls and fear of falling in patients after fragility

fracture: Results of a controlled pilot study. Preventive

Medicine, 42, 316-319.

50. Lachman, M. E., Howland, J., Tennstedt, S., et al.

(1998). Fear of falling and activity restriction: The

survey of activities and fear of falling in the elderly

(SAFE). Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Science

and Social Science, 53, 43-50.

51. Huang, T. T. (2006). Geriatric

fear of falling measure: Development and psychometric

testing. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43,

357-365.

52. Velozo, C. A. & Peterson,

E. W. (2001). Developing meaningful fear of falling

measures for community dwelling elderly. American Journal

of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 80, 662-673.

53. Tennstedt S, Howland J,

Lachman M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a

group intervention to reduce fear of falling and associated

activity restriction in older adults. J Gerontol. 1998;53B:

P384-92.

54. Belgen, B., Beninato, M.,

Sullivan, P. E., & Narielwalla, K. (2006). The association

of balance capacity and falls self-efficacy with history

of falling in community- dwelling people with chronic

stroke. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,

87, 554-561.

55. Schott, N. (2008). German

adaptation of the "activities- specific balance

confidence (ABC) scale" for the assessment of falls-related

self-efficacy. Zeitschrift Fur Gerontologie Und Geriatrie:

Organ Der Deutschen Gesellschaft Fuer Gerontologie Und

Geriatrie, doi:10.1007/s00391-007-0504-9.

56. Andersson, A. G., Kamwendo,

K., & Appelros, P. (2008).

Fear of falling in stroke patients: Relationship with

previous falls and functional characteristics. International

Journal of Rehabilitation Research. Internationale Zeitschrift

Fur Rehabilitations forschung. Revue Internationale

De Recherches De Readaptation, 31, 261-264.

57. Gillespie, S. M., &

Friedman, S. M. (2007). Fear of falling in new long-term

care enrollees. Journal of the American Medical Directors

Association, 8, 307-313.

58. Jung, D. Y., Lee, J. H.,

& Lee, S. M. (in press). A meta-analysis of fear

of falling treatment programs for the elderly. Western

Journal of Nursing Research.

59. Bandura A. Self-efficacy

mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol 1982;2:122-47.

60. Hellstrom K, Lindmark B.

Fear of falling in patients with stroke: A reliability

study. Clin Rehabil 1999;13:509-17.

61. Fessel, K. D. & Nevitt,

M. C. (1997). Correlates of fear of falling and activity

limitation among persons with rheumatoid arthritis.

Arthritis Care Research, 10, 222-228.

62. King MB, Tinetti ME. Falls

in community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc.

1995;43:1146-54.

63. Resnick, B., & Junlapeeya,

P. (2004). Falls in a community of older adults: Findings

and implications for practice. Applied Nursing Research,

17, 81-91.

64. Chou, K. L., Yeung, F. K.

C., & Wong, E. C. H. (2005). Fear of falling and

depressive symptoms in Chinese elderly living in nursing

homes: Fall efficacy and activity level as mediator

or moderator? Aging & Mental Health, 9, 255-261.

65. Gagnon, N., Flint, A., Naglie,

G., & Devins, G. M. (2005). Affective correlates

of fear of falling in elderly persons. American Journal

of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13, 7-14.

66. Niino, N., Tsuzuku, S.,

Ando, F., & Shimokata, H. (2000). Frequencies and

circumstances of falls in the National Institute for

Longevity Sciences, Longitudinal Study of Aging (NILS-LSA).

Journal of Epidemiology, 10, 90-94.

67. Warr, P., Butcher, V., &

Robertson, I. (2004). Activity and psychological well-being

in older people. Aging and Mental Health, 8, 172-183.

68. Schoenfelder, D. P., & Rubenstein, L. M. (2004).

An exercise program to improve fall-related outcomes

in elderly nursing home residents. Applied Nursing Research,

17,21-31.

69. Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay

G, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the

risk of falling among elderly people living in the community.

New Engl J Med. 1994;331:821-7.

70. Reinsch S, MacRae P, Lachenbruch

PA, et al. Attempts to prevent falls and injury: a prospective

community study. Gerontologist. 1992;32:450-6.

71. Van Haastregt, J. C., Zijlstra,

G. A., Van Rossum, E., Van Eijk, J. T., & Kempen,

G. I. (2008). Feelings of anxiety and symptoms of depression

in community-living older persons who avoid activity

for fear of falling. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,

16, 186-193.

72. Li, F., Harmer, P., Fisher,

J., McAuley, E., Chaumeton, N., Eckstrom, E., &

Wilson, N.L. (2005). Tai Chi and fall reduction in older

adults: a randomized control trial. Journal of Gerontology:

Biological Science and Medical Science, 60A(2), 187-

73. Zhang, J-G., Ishikawa-Takata,

K., Yamazaki, H., Morita, T., & Ohta, T. (2006).

The effects of Tai-Chi Chuan on physiological function

and fear of falling in the less robust elderly: An intervention

study for preventing falls. Archives of Gerontology

and Geriatrics, 42,107-116.

|