|

Introduction

There is an increasing elderly population and as a result

an increase in the number of elderly patients with significant

morbidity putting a strain on health services. This

is thought to be due to the decline in global fertility

and family size as well as the decline of mortality

in older populations. A community is regarded as relatively

old when the percentage of the population aged 65 and

above exceeds 10%(1).

In the year 2000 only some of the developed countries

experienced population aging, but it is expected that

by the year 2030 it will be experienced by all developed

countries (2).

Currently depression has a prevalence of 5-10% in the

community, and is now a major health problem in the

elderly population(3). Whether due to differences in

how people view mental health in different generations,

most of the elderly patients who present with mood symptoms

often present to their primary care practitioners as

opposed to mental health professionals(4). It is now

becoming such a prevalent illness that it is expected

to be the largest cause of disability by 2030(5).

Symptoms experienced by patients with depression have

been categorised in the ICD-10, with the key symptoms

being a persistent sadness or low mood throughout most

of the day, anhedonia, and fatigue(6). In order to diagnose

someone with depression, they must also have 2 of the

following symptoms; disturbed sleep, lack of concentration,

low self-esteem, reduced or increased appetite, recurrent

thoughts of death or suicide, agitation or retardation,

and guilt.

Several risk factors have been noted to play a role

in the aetiology of depression. Genetic factors have

a major influence, as described by a paper which showed

an estimated heritability of 37% in twin studies and

family studies indicate a two- to threefold increase

in lifetime risk of developing major depressive disorder

among first-degree relatives(7, 8). However genetic

factors are less likely to play a role in late-onset

depression than in early onset depression. Here social

circumstances may be a larger cause, with issues such

as marital status, adverse life events, unemployment

and impaired social support(9). Consistent with this

perspective, numerous social relationship domains show

an inverse association with depression and depressive

symptoms(10). Studies have shown that whilst being single

puts people at a higher risk of depression in women

than men, being married leads to a higher risk of depression

in men than women(11). Notable factors that are more

prevalent in the elderly population than the younger

population are chronic pain and medical illness. This

is because older adults will be more likely to have

substantial co-morbidities and may find these illnesses

more psychologically distressing as they can lead to

increased disability, decreased independence and a disruption

of social networks. This is particularly the case for

patients who have cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson's

disease, epilepsy, and cancer.

Later life depression is a major health problem because

it is associated with an increased risk of morbidity

as shown above, increased risk of suicide, increased

impairment be it physical cognitive or social, and greater

self-neglect. Because of these, there is an increased

mortality associated with depression in the elderly.

Data shows there are two peaks for ages at high risk

of suicide, which are 25-30 year olds and the elderly

population(12).

When looking in more depth at prevalence rates of depression

in the elderly, it has been found that whilst major

depression was rarer (1.8%), minor depression is more

common (9.8%)(13). However it has also been found that

the levels of detection and treatment of depression

are low in the elderly, which is partly due to patient's

refusal to speak freely about their depressive symptoms

as a result of stigmatised beliefs, the fact that somatic

symptoms are less useful to diagnose depression in the

elderly than in the young, and partly to a lack of access

to specialised mental health resources(14). There are

several tools to screen for depression in the elderly

population such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression,

the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Zung Self-Rating

Depression Scale, however the most reliable and valid

measure of geriatric depression is the GDS, with a specificity

of 94%(15). There are two versions of the GDS, one which

is 30 questions long and the other with 15 questions

which was used in this study. Scores ranged from 0 to

15, with scores of 0-4 showing normal result, 5-9 indicating

mild depression, and 10-15 indicating moderate to severe

depression.

Aims

1) To determine the prevalence of depression among elderly

people in Kurdistan.

2) To study the correlates of depression in late life:

Gender, Age, Education level, Economical status, Marital

status, Housing, Alcohol use, Functional status and

History of chronic medical illnesses

Patients & Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of non-institutionalized

participants, aged 65 or more years old, which is based

on multistage random sampling in three main governorates

of Kurdistan, Sulaimani, Hawler and Duhok.

Data was collected from January 2014 to June 2014 in

face to face household surveys of 650 residents of urban

and rural areas.

The structured interview included assessment of socio-demographic

characteristics, mental and physical health, functional

status, drug history, and living arrangements.

Inclusion criteria:

1. Aged 65 years and above.

2. Those who speak Kurdish.

Exclusion criteria were:

1. Patients who had other psychological problems.

2. Those who had dementia.

3. Those who speak Arabic. (those who do not speak Kurdish)

The study was approved by the scientific and the ethical

committee of the University of Sulaimani.The interviews

were conducted by the researchers directly.

Verbal consent was taken from the participant.

Assessment of depression was done using GDS-15.

Scoring of the GDS-15 ranges from 0-15. Indicating the

grade of the depression from no depression to mild,

moderate and severe depression.

We translated the GDS-15 into Kurdish, then retranslated

it to English, then compared them to ensure fewer grammar

errors.

Statistical analysis

Data concerning different variables were entered into

an Excel office spreadsheet. Data analysis was done

by using SPSS (version 20 software) computer program.

The mean values, SD of the measurements were calculated.

To test the relationship between different variables,

comparisons were made using Chi-square testing. All

P- values were based on 2-sided tests, and p < 0.05

was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean + SD age of study

population was 71.5 + 6.8 years. About 73.3% of them

were below 75 years and 25.7% 75 years old and above.

The majority of the study population were male (61.2%)

and mostly people were married(68.9%). More than half

of the study population were living in Sulaimani (53.5%),

with the remainder living in Hawler and Duhok. Eighty

seven percent of the study population were living in

an urban area. In this study, most of the participants

had 5 children and more (64.5%).

The majority of the study population

lived in their own homes in the community (96.6%), with

only 10.1% of participants living by themselves. Only

27.8% of the study population were in employment, with

moderate economic status dominating (51.5%).

56.0% in this study were ex-smokers

with 21.2% had never smoked. Most study participants

(83.3%) were mobilised without any aids, 14.1% walked

with a stick, and only 2.6% used other aids. About 6.1%

of them had a history of drinking alcohol and 75.5%

used medications for chronic diseases. Across the whole

study 67.2% used 1-2 medications and 32.4% used 3 medications

and above. The percentages of a positive history of

diabetes, hypertension, stroke, ischemic heart disease,

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinson's disease,

and other diseases were 26.2%, 46.6%, 6.5%, 10.8%, 11.2%,

7.4%, 30.5% respectively. The mean duration of disease

in the study population was 2.3 + 0.7 years. The mean

times of attacks of disease were 1.7 + 1.3. Despite

multiple co-morbidities about 72% of the population

had no history of hospital admission.

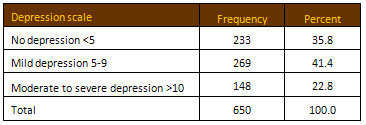

The results show that

most of the study population had mild depression (41.4%),

Table 1.

Table 1: Depression scale according to the severity

of depression

Although most of the study

population who were selected from both the community

and nursing homes had depression (scored 5 - 15), the

relationship between place of abode and depression was

still statistically not significant (P> 0.05). The

relationship between area of residence and depression

scale was also studied and the association was statistically

significant (P=0.031). Most of the study population

in Sulaimani, Duhok, and Hawler had depression (scored

5 - 15), but the highest percentage was in Duhok 73.9%.

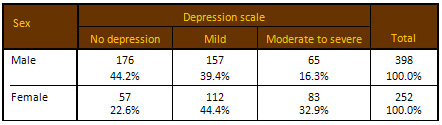

The relationship between gender

and depression scale was statistically highly significant

(P<0.01). Females had a higher percentage of depression

(77.4%) than males (55.8%).

The association between gender and depression scale,

according to the severity of depression, was also studied.

The relationship was found statistically highly significant

(P<0.01), i.e. females also had higher percentages

of both (mild) and (moderate to severe) depression (44.4%

and 32.9%) than males (39.4% and 16.3%) respectively,

Table 2.

Table 2: Gender and

grade of depression

Chi= 39.70, df= 2, P value=

0.000

Our study shows that depression

was more prevalent in those who live in a rented house

or other accommodation (81.1% and 78.7% respectively)

in comparison with those who owned their home (60.5%).

The relationship between type of housing and depression

scale was statistically highly significant (P<0.012).

The association between the history of alcohol use and

depression was studied. It was statistically significant,

P<0.05. Depression was lower in those with a history

of alcohol use (48.7%) in comparison with no alcohol

use (65.3%), P=0.036.

The relationship between the

history of hospital admissions in the last 12 months

and depression scale was statistically highly significant,

P=0.001. Additionally, the highest percentage of depression

was in those with a history of hospital admission (77.1%),

Lastly, a statistically highly significant association

was found between the number of medications used by

the individual and the depression scale, P<0.01.

The highest percentage of depression was found in those

who used 3 medications and above (80.0%).

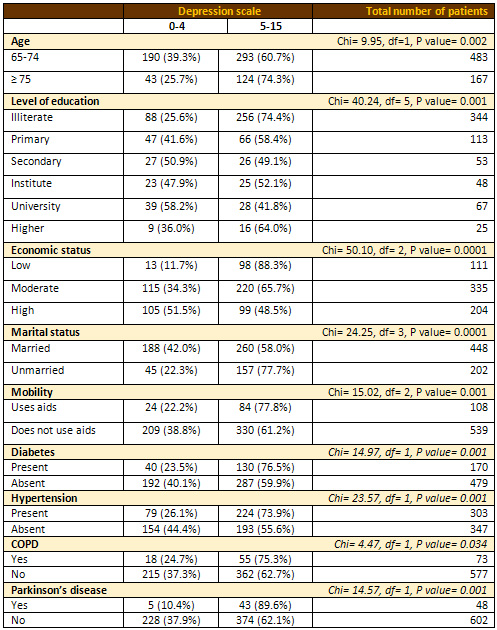

Table 3

Discussion

This cross sectional study demonstrates that there is

a high prevalence of depression in the elderly, with

64.2% of participants affected, the majority of whom

were suffering mild depression (41.4%) and just under

a third (22.8%) moderately to severely depressed. Given

the majority of the study population were male (61.2%)

and the rate of depression in women was found to be

significantly higher (77.4% vs 55.8%, P-value 0.001),

this may even be a disproportionately low figure. Whilst

this supports the hypothesis the notion that depression

is a mounting issue, it is even more than would be expected.

Furthermore, none of those identified as depressed had

a pre-existing diagnosis of depression. Such high percentage

might be the possibility of Geriatrics Depression scale

questioning only has specificity and sensitivity in

diagnosing depression if asked in English to an English

speaking subjects with western social values and standard

of education in society. However the questionnaire in

this study was transplanted to Kurdish and the subjects

were all Kurdish with middle-eastern social values and

standard of education. Whether the subjects understood

the reasoning for Geriatric Depression Scale questions

when asked would have made a difference.

According to a systematic review of community-based

studies on depression in later life from The Netherlands,

higher percentages of depression were demonstrated in

women(16). The overall prevalence rates were also markedly

lower than found in this study, with the average at

13.5% and a range of 0.4-35%.9 Given the review noted

correlation of low socio-economic situation with depression

and the discrepancy of prevalence between these studies,

it is reasonable to hypothesize that there may have

been higher incidence of such risk factors in this study

population(16).

A review from Brazil, a more comparable developing country,

showed that depression was more prevalent in the younger

elderly (aged 65-74) with no pronounced difference between

the sexes(17). As our study's participants were mostly

under 75, with a mean age of 71.5, this might be one

explanation for its finding such high levels of depression.

Compared to the study in Brazil, the prevalence of depression

in Kurdistan was actually higher in late elderly age

group (75 years and over) (74.3%) compared to early

elderly age group (60.7%), P-value=0.002. Additionally,

a similar study in The Netherlands revealed that the

late elderly age group is at higher risk for developing

depression(18).

That being said, the proportion of participants with

mild vs moderate and severe depression is supported

by an Iranian study of elderly people in a nursing home

in Tehran that revealed higher rates of mild depression

(50%) compared to moderate and severe depression (29.5%

and 10.7% respectively)(19). This data has been mirrored

in other cases, where a study in Canada also revealed

more prevalent rates of mild depression compared to

major depression (2.6% and 4% respectively)(20).

A study in Lebanon showed that elderly people with dementia

were more likely to be depressed, with a prevalence

of 41.2% compared to 14.5% in those without cognitive

impairment(21). Though this study did not specifically

comment on dementia, and given the low proportion that

were from a nursing home it might be assumed to be low,

it would be interesting to have this data. Nevertheless

this supports the evidence that disease is a risk factor

for depression, as shown in our study with higher rates

of depression in those with COPD, Parkinson's, hypertension,

diabetes, hospital admission within a year, reduced

mobility and polypharmacy (with statistical significance

shown for all but COPD).

An interesting point was that smoking did not correlate

with mood, and those who drank alcohol had less risk

of developing depression in our study (P-value 0.036).

There is no data in this study and limited data in general

on whether there is any correlation between religion

and depression, but it may be a factor and even implicated

in the link with alcohol, particularly in this study

given the population is predominantly Muslim.

Residential and nursing home residents generally have

poorer health than those in their own homes and so by

this reasoning would be more at risk of depression.

Supporting this, a study from Turkey exposed that depression

among the elderly population living in nursing homes

was indeed more prevalent than for those living at their

own home, 41% and 29% respectively(22). However living

in nursing home in this study did not increase the chance

of depression (P-value 0.654), though this may be due

to smaller number of nursing home participants.

The prevalence of depression among elderly Pakistanis

in a similar cross-sectional study found higher rates

of depression among those with multiple diseases, financial

problems and taking numerous medications(23). A study

in Brazil has concurred with this point, showing depression

is significantly more common in the presence of medical

diseases, poor functional capacity, and hospital admissions

in the last 12 months.10 Furthermore, in a big Saudi

study involving 7,970 people, depressive symptoms were

found in about 40% and was also shown to be strongly

associated with poor functional capacity and multiple

medical diseases with polypharmacy(24). Additionally

higher prevalence of depression was seen in those with

poor housing conditions, poor educational status, living

in remote areas, the unemployed, divorced or widowed

and women(24). This study highlighted that the single,

widowed, divorced, those with poor economic status,

the illiterate and interestingly also the highly educated,

are more likely to develop depression. Further to this,

those who rented houses rather than owned them were

found to have a higher prevalence.

Conclusion

This study highlights the fact

that depression is a common condition in the elderly

population of Kurdistan. Life expectancy in Kurdistan

is already increasing and it will continue to do so

as part of world-wide increase in the elderly population.

Among the health problems of this age, affective disorders

are becoming apparently common. In order to cope with

these changes, improvement in or even establishment

of health care services to this age group is an essential

health strategy focus that needs to be on both under

and post graduate training in care of the elderly mental

health and public awareness about depression in the

elderly. Health systems must be designed to meet the

needs of the population served.

References

1. Gavrilov L.A., Heuveline

P., Aging of Population, The Encyclopedia of Population.

New York, Macmillan Reference USA, 2003

2. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Population Division (2015), World Population

Ageing, 2015

3. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of

psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on

clinically depressed older adults: A meta-analysis.

Aging and Mental Health. 2007;11:645-657.

4. Unützer J, Katon W, Sullivan M, Miranda J. Treating

Depressed Older Adults in Primary Care: Narrowing the

Gap between Efficacy and Effectiveness. The Milbank

Quarterly. 1999;77(2):225-256.

5. Mathers C, Loncar D. Projections of Global Mortality

and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine.

2006;3(11):e442.

6. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural

Disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research [Internet].

10th ed. Geneva: world health organisation; 2017 [cited

1 February 2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/GRNBOOK.pdf

7. Sullivan P, Neale M, Kendler K. Genetic Epidemiology

of Major Depression: Review and Meta-Analysis. American

Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1552-1562.

8. Lohoff F. Overview of the Genetics of Major Depressive

Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2010;12(6):539-546.

9. Barger S, Messerli-Bürgy N, Barth J. Social

relationship correlates of major depressive disorder

and depressive symptoms in Switzerland: nationally representative

cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1).

10. Cacioppo J, Hawkley L, Ernst J, Burleson M, Berntson

G, Nouriani B et al. Loneliness within a nomological

net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research

in Personality. 2006;40(6):1054-1085.

11. Umberson D, Montez JK. Social Relationships and

Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy. Journal of health

and social behavior. 2010;51(Suppl):S54-S66.

12. Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in Older

Adults. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2011;34(2):451-468.

doi:10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.002.

13. Beekman A T, Copeland J R, Prince M J, Review of

community prevalence of depression in later life, The

British Journal of Psychiatry Apr 1999, 174 (4) 307-311;

DOI: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307

14. Lyness J, Cox C, Curry J, Conwell Y, King D, Caine

E. Older Age and the Underreporting of Depressive Symptoms.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43(3):216-221.

15. Yesavage J, Brink T, Rose T, Lum O, Huang V, Adey

M et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression

screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric

Research. 1982;17(1):37-49.

16. Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ. Review of community

prevalence of depression in later life. The British

Journal of Psychiatry 1999; 174:307-311.

17. Luis BS, Baxter S, Gerada GF, Fabio G. Depression

morbidity in later life: Prevalence and correlates in

a developing country. The American Journal of Geriatric

Psychiatry 2007;15 (9): 790-799.

18. Licht-Strunk E, van der Kooij KG, van Schaik DJ

F, van Marwijk HWJ, van Hout HPJ, de Haan M. and Beekman

ATF. Prevalence of depression in older patients consulting

their general practitioner in The Netherlands. Int.

J. Geriat. Psychiatry 2005; 20: 1013-1019.

19. Nazemi L, Skoog I, Karlsson I, Hosseni S, Hosseni

M, Hosseinzadeh MJ, Mohammadi MR, Pouransari Z, Chamari

M, Baikpour M. Depression, prevalence and some risk

factors in elderly Nursing Homes in Tehran, Iran. Iran

Journal of Public Health 2013; 42(6): 559-569.

20. Østbye T, Kristjansson B, Hill G, Newman

SC, Brouwer RN, McDowell I. Prevalence and predictors

of depression in elderly Canadians: The Canadian study

of Health and Aging. Chronic diseases in Canada 2005;

26(4): 93-99.

21. El Asmar K, Chaaya M, Phung KTT, Atweh S, Ghosn

H, Khoury RM, Prince M, Waldemar G, Anxiety among older

adults in Lebanon: preliminary data from Beirut and

Mount. Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the

Alzheimer's Association, 2014; 10(4): 595-P595

22. Tsuang MT, Faraone SV. The genetics of mood disorders.

Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1990.

23. Ganatra HA, Zafar SN, Qidwai W, Rozi S. Prevalence

and predictors of depression among an elderly population

of Pakistan. Ageing and Mental Health 2008; 12(3): 349-356.

24. Al-shammari SA, Al-Subaie A. Prevalence and correlates

of depression among Saudi elderly. International Journal

of Geriatric Psychiatry 1999; 14(9): 739-747.

|