|

Introduction

The portion of frail people in the community is increasing.

Since the definition of this syndrome is in development,

the clear numbers of frailty are not well known. A systematic

review estimated the prevalence of frailty in the community

ranging between 4-59.1% (1), which depended on the definition

of frailty. Based on the Fried model it was found as

9.9% and 44.2% for frailty and pre-frailty respectively

(2,3).

In Turkey recent studies have reported different frequencies.

Akin S et al (4) reported in community-dwelling Turkish

elderly a prevalence of frailty, pre-frailty and non-frailty

measured with the modified Fried Frailty Index as 27.8,

34.8, and 37.4 %, respectively and 10, 45.6, and 44.4

% with FRAIL scale. Eyigör et al. (5) found 39.2

and 43.3 % of patients attending outpatient clinics

of 13 university and training hospitals as frail and

pre-frail, respectively. Çakmur H (6) reported

in a rural city sample from East Turkey 7.1% frail and

47.3% pre-frail according to Fried Frailty criteria.

Frailty is a difficult process, which affects the patient

and the garegivers. Conditions, which develop with aging

and disablity are a burden to the person and their family.

Preventive measures have been recommended in the past

to overcome this problem (3). Proper and early intervention

might ameloriate the outcomes of this problem, which

is proven by evidence (3).

The identification of frailty is important and family

practice plays a central role. The family physician

can deliver an holistic approach to manage frailty.

Low-resourced settings and places with accessibility

problems might especially benefit from this (7,8), but

established well-developed health care systems also

could profit from a person-centred approach.

The detection of frailty could follow an opportunistic

pathway, where formal and informal health care and social

service professionals could be useful. Further services

of professionals, who are not especially trained for

this risk group (midwifes, mother and child care nurses)

could be utilised for this purpose (3). The information

reftrieved from the caregiver might be an important

source for early identification of these patients, who

are in need of help and support. A patient-centred approach

focusing on self-preceived care needs is a relatively

unknown approach of needs assessment in frail elderly.

It is as important as the geriatric assessment (9,10).

So far, we are not aware of any study, which is evaluating

the contribution of caregivers for the identification

of the frail person at home.

This study aims, to investigate by asking attendants

to a family practice, the SARC-F scores of frail people

at home and the opinion of caregivers on the care of

the frail.

Materials

and Methods

Research design: This cross-sectional study included

1,016 patients, who consecutively visited a family practice

outpatient clinic in Antalya, Turkey and who voluntarily

participated in this study. The study took place between

March-October 2015. The

participants had educational level of at least primary

school level.

The questionnaire had two steps. Firstly all participants

were asked if they had a frail person at home for whom

they were in charge of. The definition of frailty was

made according to the definition stated in the document

(Frailty is a multidimensional geriatric syndrome characterized

by increased vulnerability to stressors as a result

of reduced capacity of different physiological systems.

It has been associated with an increased risk of adverse

health-related outcomes in older persons, including

falls, disability, hospitalizations and mortality, and

has further been associated with biological abnormalities

(e.g. biomarkers of inflammation) regardless of the

definition used to assess frailty. This clearly suggests

that frailty is influenced by a number of pathophysiological

modifications involving the body's diverse physiological

systems. http://www.frailty.net/frailty-at-a-glance)

(11). The participants gave verbal consent.

Instrument development:

The questionnaire was developed as follows: Firstly,

the literature (1,2,12,13) and short frailty questionnaires

(i.e. SARC-F) were evaluated (14). The draft questionnaire

was evaluated by independent experts from family practice

with a special interest in elderly care and frailty

and afterwards pilot-tested with a total of ten patients.

The pilot survey was excluded from the final database.

This process enabled refined and improved items with

clarity in the wording of the survey.

The survey had the following

sections:

a. Demographics: 2 open-ended (i.e. age

of the participant and frail elder) and 7 closed-ended

questions (i.e. gender, marital status, frail elder

at home; age, drugs, polypharmacy, and disease of the

frail elder);

b. SARC-F items (15,16,17): Strength,

assistance walking, rise from a chair, climb stairs,

and falls are included in the SARC-F items. Scores range

from 0-10. Each item counts for 0-2 points. Total score

ranges are between 0 = best to 10 = worst. Outcome of

total score was dichotomized to symptomatic (frail)

(4+) and healthy (0-3) status. In this study the caregiver

was asked "how much difficulty (the older person

at home) had lifting or carrying 5 kg" (0 = no

difficulty, 1=some, and 2 = a lot or unable to do);

"how much difficulty (the older person at home)

had walking across a room" (0 = no difficulty,

1=some difficulty, and 2 = a lot of difficulty, use

aids, or unable to do without personal help); "how

much difficulty (the older person at home) had transferring

from a chair or bed" (whether they used aids or

needed help to do this) (0 = no difficulty, 1=some difficulty,

and 2 = a lot of difficulty, use aids, or unable to

do without help); "how much difficulty they had

climbing a flight of 10 steps" (0 = no difficulty,

1=some, and 2 = a lot or unable to do),and falls was

scored a 2 for respondents who reported falling four

or more times in the past year, 1 for respondents who

reported falling 1-3 times in the past year, and 0 for

those reporting no falls in the past year.

c. Attitudes and Perception

on the Care of their Frail Elder:

Participants were asked to rate the following questions

on a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly

agree, scored from "1" to "5"):

"I feel competent in caring for my frail elder",

"I would follow the treatment recommendations of

my frail patient", "I would seek appropriate

support for my frail elder", "Immobile, frail

elder need home health services", "The family

plays an important role in the early diagnosis of frailty",

"Mobile technologies play an important role in

the care of frail elders", and "Family members

play an important role in the care of frail elders".

Statistical analysis:

Data of this study were analysed with descriptive statistics;

chi-square for categorical variables and Spearman's

rho correlation. The level of significance was set at

alpha=0.05.

Results

The age of caregivers of frail people were 52.1 (SD=12.66;

min-max=19-83; n=1016). Most were women (N=762; 74.9%;

men n=256;25.1%) and married (n=722; 75.1%; divorced/widowed,

n=165;17.2%; single, n=74; %7.7; missing value, n=57,

5.6%)). One hundred and sixty nine (16.8%; n=14 missing

values, %1.4) patients indicated to have a frail person

at home.

The age was 78.2 (SD=8.21; min-max=55-98;

n=170). Most were women (n=124; 75.6%; male, N=40; 24.4%;

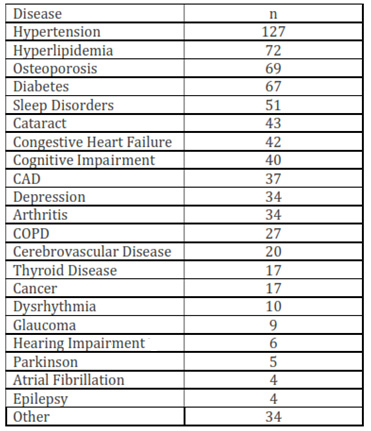

n=854, %83.9 missing values). Disease of the frail elderly

is shown in Table 1 (median= 1 disease; min-max=0-4).

Table 1: Diseases of the frail person

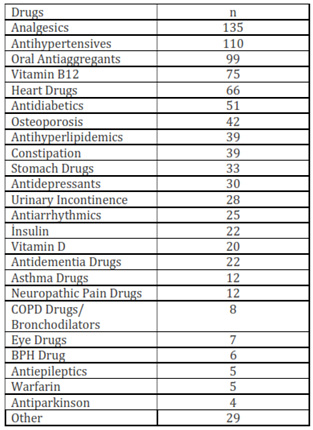

Most frail persons (84%) used

more than four drugs a day. The drugs used by the frail

patient are shown in Table 2 (median 6 drugs; min-max=0-14).

One hundred and twenty nine (75%) patients used four

and more drugs.

Table 2: Drugs used by the frail patient

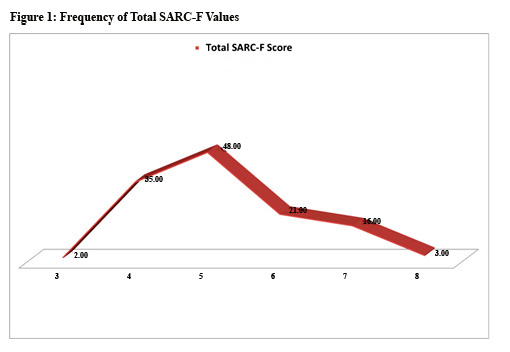

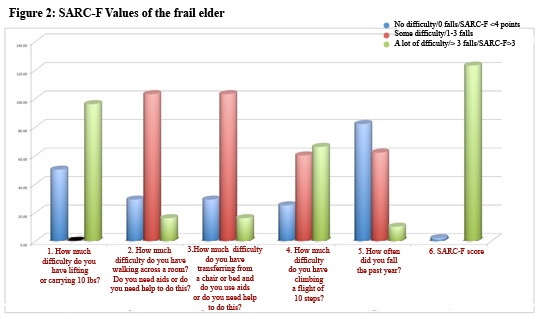

Sarc-F Total Score was found

to be 5.2 (median=5; SD=1.1; min-max=3-8; n=125) (Figure

1). The frequency distribution of the SARC-F values

of frail people are shown in Figure 2 (SARC-F Score

>=4=99.8%; 4-6=85.2%). SARC-F>=4 was prevalent

in 123 elderly, which was 12.1% of all participants

in this study.

Figure 2: SARC-F Values

of the frail elder

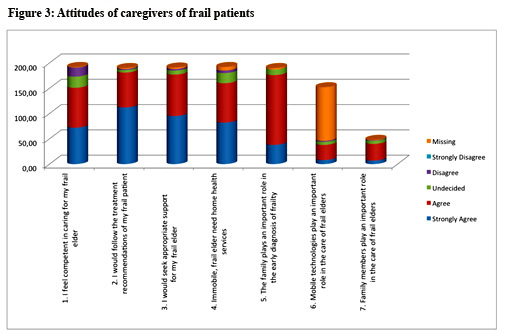

The attitudes of caregivers

of frail people are shown in Figure 3.

The gender of the participants

showed no difference between their age, their frail

elders' age and SARC-F total score (p>0.05). The

gender and the number of medicaments used did not have

an effect on the SARC-F total score (p>0.05).

Total SARC-F score correlated at medium level with the

falls item (r=0.70,p<0.05), walking item (r=0.46,p<0.05),

transfer item (r=0.44,p<0.05), and stairs item (r=0.66,p<0.05).

Attitude of competency to provide care item, correlated

at medium level with following treatment recommendation

item (r=0.49,p<0.05), at low level with seeking appropriate

care item (r=0.33,p<0.05), and at low level with

family members play important role item (r=0.17,p<0.05);

following treatment recommendation item showed medium

level correlation with seeking appropriate care item

(r=0.51,p<0.05), and low level with the role of mobile

technology item (r=0.21,p<0.05); the seeking appropriate

care item showed low level correlation with the early

diagnosis item (r=0.19,p<0.05) and with the role

of mobile technology item (r=0.22,p<0.05); the home

health care item showed low level correlation with role

of mobile technology item (r=0.25, p<0.05); the early

diagnosis item showed low level correlation with role

of mobile technology item (r=0.23, p<0.05) and the

important contribution of the family item (r=0.32, p<0.05).

The falls item of SARC-F showed low-medium level correlation

with the competency to provide care item (r=0.34,p<0.05);

the power item of SARC-F showed low level correlation

with the competency to provide care item (r=0.18,p<0.05);

total SARC-F score correlated at low-medium level with

the competency to provide care item (r=0.31,p<0.05)

and low level with the following treatment recommendation

item (r=0.18,p<0.05).

Discussion

This study showed that the majority of frail people

at home were suffering from at least one (0-4) chronic

condition and 75% used more than four drugs (polypharmacy).

According to SARC-F evaluation most were at pre-frail

level. The domains on upper extremity strength and climbing

stairs were the weakest, which could be improved with

exercise. Short distance walking, transfers and falls

were better. Participants were in agreement with the

statement "I feel competent in caring for my frail

elder", "I would follow the treatment recommendations

of my frail patient", "I would seek appropriate

supprt for my frail elder", "Immobile, frail

elder need home health services", "The family

plays an important role in the early diagnosis of frailty",

"Mobile technologies play an important role in

the care of frail elders", and "Family members

play an important role in the care of frail elders".

Participation in the last two items was low.

The multi-morbidity of our patients in the study was

not high. Cesari et al. report that multimorbidity might

show a moderating effect on related health-care utilisation,

than patients who are not diagnosed with multimorbid

conditions (1). In this case, patients without multi-morbidity

might be at risk of being undetected for frailty condition.

But even if the patient is having a disability or comorbid

condition the diagnosis of frailty does not take this

into consideration. The more the number of chronic conditions

the higher the risk of frailty has been observed (18).

Heart failure, COPD, chronic kidney disease, urinary

incontinence, and cognitive impairement might present

higher prevalence of frailty (19).

But the relation of frailty to aging and chronic conditions

is not clear (18).

According to SARC-F evaluation most were at pre-frail

level. SARC-F has been shown to be a good predictor

of poor muscle function, which has a good correlation

with knee strength and grip strength. It also shows

good correlation with FRAIL scale, which is a self-administred

tool (17). In our study, the domains on upper extremity

strength and climbing stairs were the weakest, which

could be improved with exercise. Short distance walking,

transfers and falls were better.

Our study showed a predominance of women with frailty,

but this observation did not reveal any significant

difference concerning SARC-F score, therefore indication

that the level of frailty was equal in both genders.

A higher prevalance of frailty in women has been also

observed in the literature (1,19).

Most frail people at home were at pre-frail level (SARC-F

Score 4-6=85.2%). In a study, which performed home care

assessments 21.3% were found prefrail and 26.9% frail

(20).

Caregivers were confident, compliant and empowered concerning

the care for their patients. They are aware of home

health care services and would also apply for these.

Another study reported that caregivers, who cared for

the frail were more prone to leave, but caring for pre-frail

patients did not provoke this feeling (20), which is

supported in our findings.

The determination of care needs of frail people is recommended

due to its potential to improve the care of this risk

group. The evaluation of self-perceived health needs

might be a good starting point (21). The results of

our study also provided valuable information on the

situation of patients, who cared for their frail elders

at home. These findings have in our opinion two important

implications. There is a potential need for interventions

to prevent frailty in elderly people at home and a need

to follow-up the health and burden of caregivers. Both

approaches certainly exceed the capacity of family practice.

These need to be managed by a multi-disciplinary healthcare

and rehabilitation team, where the family physician

should be a member. The family physician and his team

could contribute to the management of this problem by

screening caregivers, healthy (13,22), and possible

frail elders, performing home visits, training caregivers

concerning warning signs of frailty, and empowering

elderly people concerning their own health (1,23).

Acknowledgment:

This study has been supported by the Akdeniz University

Research Management Unit.

References

1. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC.

Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons:

A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1487e1492.

2. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older

adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci

Med Sci 2001;56:M146eM156.

3. Cesari M, Prince M, Thiyagarajan JA, De Carvalho IA,

Bernabei R, Chan P, Gutierrez-Robledo LM, Michel JP, Morley

JE, Ong P, Rodriguez Manas L, Sinclair A, Won CW, Beard

J, Vellas B.Frailty: An Emerging Public Health Priority.

Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016 Jan 21. pii: S1525-8610(15)00766-5.

doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.12.016. [Epub ahead of print]

4. Ain S, Maz?c?oglu MM, Mucuk S, Gocer S, Deniz ?afak

E, Arguvanl? S, Ozturk A. The prevalence of frailty and

related factors in community-dwelling Turkish elderly

according to modified Fried Frailty Index and FRAIL scales.

Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015 Oct;27(5):703-9. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0337-0.

Epub 2015 Mar 12.

5. Eyigor S, Kutsal YG, Duran E, Huner B, Paker N, Durmus

B, Sahin N, Civelek GM, Gokkaya K, Do?an A, Günayd?n

R, Toraman F, Cakir T, Evcik D, Aydeniz A, Yildirim AG,

Borman P, Okumus M, Ceceli E; Turkish Society of Physical

Medicine and Rehabilitation, Geriatric Rehabilitation

Working Group. Frailty prevalence and related factors

in the older adult-FrailTURK Project. Age (Dordr). 2015

Jun;37(3):9791. doi: 10.1007/s11357-015-9791-z. Epub 2015

May 7.

6. Çakmur H. Frailty among elderly adults in a

rural area of Turkey. Med Sci Monit. 2015 Apr 30;21:1232-42.

doi: 10.12659/MSM.893400.

7. De Lepeleire J, Iliffe S, Mann E, Degryse JM. Frailty:

An emerging concept for

general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:e177-182.

8.Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, et al. The burden of disease

in older people and implications for health policy and

practice. Lancet 2015;385:549-562.

9. Walters, K., Iliffe, S., Tai, S. S., & Orrell,

M. (2000). Assessing needs from patient, carer and professional

perspectives: The Camberwell Assessment of Need for Elderly

people in primary care. Age and Ageing, 29, 505-510.

10. Hoogendijk EO, Muntinga ME, van Leeuwen KM, van der

Horst HE, Deeg DJ, Frijters DH, Hermsen LA, Jansen AP,

Nijpels G, van Hout HP. Self-perceived met and unmet care

needs of frail older adults in primary care. Arch Gerontol

Geriatr. 2014 Jan-Feb;58(1):37-42. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.09.001.

Epub 2013 Sep 12.

11. "frailty at a glance. Accessed: 01.01.2016. Accessed

at: http://www.frailty.net/frailty-at-a-glance.

12. Fit for Frailty - consensus best practice guidance

for the care of older people living in community and outpatient

settings - a report from the British Geriatrics Society

2014.

13. Yaman A, Yaman H. Frailty in Family Practice: Diagnosis

and Management (in Turkish). Ankara Med J, 2015, 15(2):89-95.

14. Morley JE, Cao L. Rapid screening for sarcopenia.

J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2015 Dec; 6(4): 312-314.

Published online 2015 Nov 18. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12079

15. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm

T, Landi F, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition

and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on

Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010; 39: 412-423.

16. Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S, Morley

JE, Newman AB, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition

in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence,

etiology, and consequences. International Working Group

on Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011; 12: 249-256.

17. Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L,

Morley JE. SARC-F: a symptom score to predict persons

with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes.

Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2015; DOI:

10.1002/jcsm.12048

18. Heckman G, Molnar FJ.Frailty: Identifying elderly

patients at high risk of poor outcomes. Can Fam Physician.

2015 Mar;61(3):227-31.

19. Lee L, Heckman G, Molnar FJ. Frailty: Identifying

elderly patients at high risk of poor outcomes. Can Fam

Physician. 2015 Mar;61(3):227-31.

20. McKenzie K, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Martin L. Using an

accumulation of deficits approach to measure frailty in

a population of home care users with intellectual and

developmental disabilities: an analytical descriptive

study. BMC Geriatr. 2015 Dec 18;15:170. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0170-5.

21. Hoogendijk EO1, Muntinga ME, van Leeuwen KM, van der

Horst HE, Deeg DJ, Frijters DH, Hermsen LA, Jansen AP,

Nijpels G, van Hout HP. Self-perceived met and unmet care

needs of frail older adults in primary care. Arch Gerontol

Geriatr. 2014 Jan-Feb;58(1):37-42. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.09.001.

Epub 2013 Sep 12.

22. Yaman A, Yaman H. The Cognitive Evaluation of Elderly

Individuals in Family Practice. KONURALP TIP DERGISI 2015;

7 (2): 121-123.

23. Ilinca S, Calciolari S. The patterns of health care

utilization by elderly Europeans: frailty and its implications

for health systems. Health Serv Res. 2015 Feb;50(1):305-20.

doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12211. Epub 2014 Aug 19.

|